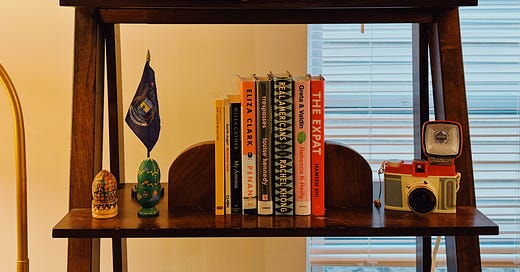

My Top 8 Novels for 2024

OK one of them is a short story collection but rules are for squares.

Confession: Prior to this year, I did not track my reading in any systematic way. I hauled a curated library of books I loved between apartments, and the rest of my reading happened on a Kindle, which tracked what I read when (and presumably a whole lot else) for me. And I’ve always had an aversion to GoodReads because its “out of five stars” system just does not jive with how I process the world. So, I just read, read for myself, and didn’t stress too much about “keeping track.”

This year, however, I did make a spreadsheet and kept it up to date, so now I get to write my first ever Top Novels of the year! And you get to read it, dear reader! I guess organization does pay off …

Now, as you’ll notice from my first selection, which was published in 1918, this is not a Top Novels of the Year list, but a Top Novels I Read This Year list. And if you’ve been reading a lot of other Top Novels of 2024 lists, I’m certain you’ll see a few common titles missing. While a few of them (ahem, All Fours) I did read and did not like, most of them (Rejection, Headshot, Martyr!, Small Rain) are books I simply haven’t read yet. Hardbacks are expensive, y’all, and I rely on my fellow avid readers and writers to tell me which are actually worth my $28. And conveniently for you, dear reader, all but three of my Top Reads are out in paperback now, and Rebecca K. Reilly’s Greta & Valdin will get its paperback release in February 2025 — if you can wait that long to read it.

OK, I’m getting ahead of myself. Onto the list!

EDIT: After thinking about it, I actually changed my mind and replaced one of my picks — Willa Cather’s My Ántonia — with Jordan Tannahill’s The Listeners. When I put this list together, I’d literally just finished The Listeners and thought I might have a recency bias, but no, that novel is fucking brilliant. No shade to Willa Cather, obviously, and I’d still pack My Ántonia if I were being sent to a desert island. But over six months later, I realized The Listeners has to go on record as one of my favorite novels of the year. - 5/22/25

The Listeners by Jordan Tannahill (2021)

What does it mean to be delusional — and what does it matter? There are a lot of questions in Jordan Tanahill’s bombastic novel, The Listeners, but this is the one I felt the novel circling back to at the end. And yes, there’s something dangerous in even asking some of the questions it raises, but what else is art for?

Our narrator, Claire, begins hearing a low, constant hum that no one else in her life — not her husband, not her daughter, not her best friend or her colleagues at work — can hear. Is it in her head, or is it in the air? In a desperate search to find the answers she needs, she connects with a student in one of her English classes who can also hear the hum, blazing right through the optical red flag of having this kind of an off-campus friendship and into a support group for others who can, supposedly, hear the hum. But who’s hosting them, and whether they’re all for the same reasons, begins to unravel their lives outside the group, lives where hearing the hum isn’t just doubted, but a cause for concern. If they can’t trust their own minds, though, who or what can they trust?

What struck and stuck with me about this novel is how Tannahill — a playwright with an incredible gift for plotting — sticks so closely to the conspiracy of “the hum” that it lets the novel speak to a much broader range of possible delusions, like religion and the belief in an unseeable God. And while Tannahill is Canadian, he captures the way these questions ricochet off each other in American culture with a perception maybe only an outsider could bring to our culture.

As a purchasing note, this novel never got published in the U.S. (I got my copy from a little free library — thanks neighbor!), which unfortunately means Amazon is the only place I’ve been able to track down a paperback. You can also order it from the U.K. via Waterstones, or you can purchase an eBook through Bookshop.org.

#7: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (2023)

God, I love a good tragic romance, and Louise Kennedy’s Trespasses is as good as it gets. Set outside Belfast during the later years of The Troubles, it’s about a young Catholic woman, Cushla, who begins an affair with an older, married Protestant man, Michael. Michael is a barrister who represents IRA members, so he’s more than sympathetic to the oppression and discrimination Cushla faces as a Catholic, but even that sympathy can’t ease all the political tensions between them. Despite those, however, they continue falling into a tender, heart-wrenching love affair, one that aspires to endure through the brutality of ongoing civil war.

In addition to Cushla’s love affair with Michael, Kennedy opens up the rest of her life — the family bar she tends with her gruff older brother; her loving but strained relationship with her depressed, widowed mother; and the tensions erupting at the school where she teachers, focused on one of her beloved but troubled students. Kennedy’s blunt, evocative prose creates an exquisite portrait of a place and the people living, or trying to live, their lives there. While it’s not exactly an uplifting read, it is one of those novels that allows tragedy to be beautiful, which is life-affirming in its own devastating way.

#6: The Expat by Hansen Shi (2024)

Like Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, Hansen Shi’s The Expat uses the framework of an espionage novel to tell a deeper story about society and our place in it. The Expat’s protagonist and narrator, Nick, is a Chinese-American living in San Francisco and working for GM, where he feels trapped beneath a “bamboo ceiling.” To vent his frustration, he spends most of his free time in an online community of contract hackers, where he meets Vivian, an intelligent and striking woman who entrances him into joining her in China for a trip to meet her investor uncle, Bo. For Nick, this isn’t just a romantic trip; Vivian is offering him an entry point to China, where Nick hopes to feel more at home than he does in America, and a group of leaders who will finally recognize his potential.

Since The Expat is so tightly-plotted, I don’t want to give much more away, but I’m sure you can spot the places where Nick’s journey detours through far more twists and turns than he expects. It’s extraordinary watching Shi write a mystery around the inner workings of corporate espionage, the intelligence community, and big bets on future technologies, and as someone who comes from Big Tech, it’s even more extraordinary how accurate this mystery felt. But what made The Expat so special to me is Shi’s portrayal of Nick and all his vulnerabilities. Even in the depths of globalized capitalist hell, Nick is still searching for belonging, love, and purpose, and those emotional questions propel The Expat along as much as its edge-of-your-seat plot. By far, this was the best literary espionage/noir novel I read this year, and perhaps since I first read The Quiet American.

#5: Don’t Look at Me Like That by Diana Athill (1967)

“When I was at school I used to think that everyone disliked me, and it wasn’t far from true.”

Thus begins Meg Bailey’s account of her young life, and it’s one of my favorite coming-of-age stories ever. Set in England right after World War II, Don’t Look at Me Like That carries us from Meg’s small town girlhood, where she’s constantly out of place, to her young adulthood as an illustrator in London, where she makes her own life, colorful and strange, amidst the cacophony of the city. There’s a vitality in these pages, with a cast of singular and often-hilarious characters from all walks of life, many of whom move through the “rooming house” (aka group house) Meg moves into, and a live-wire passion running through her personal and professional adventures. It would be a perfectly charming novel — if Meg’s blossoming sense of herself didn’t come in part from an affair with her childhood best friend’s husband.

In 2024, novels about women doing bad and unhinged things are everywhere, but what stuck with me about Don’t Look at Me Like That is how matter-of-fact Diana Athill’s rendering of Meg’s life is. There’s no wallowing, no self-pitying, no wishing she could be someone else. Rather, Meg’s attitude is to understand, not justify, herself, and there’s something so refreshing about her tone. Don’t Look at Me Like That is a spiky, brilliant, and timeless story about the mistakes we make as we become ourselves — and how life would be ever so dull without them.

#4: Earth Angel by Madeline Cash (2023)

In Earth Angel, Madeline Cash has created her own theater of the absurd, an equally hilarious and disturbing world tour of our times. In “Slumber Party,” a woman approaching her 30th birthday discovers none of her friends want to join her for a cabin weekend, so she hires a group of friends through an app, then gets fleeced via an itinerary of Bitcoin mining, seances, and corporate salads. In “Earth Angel,” Anika is stuck between her injured, Adderall-addicted younger brother, her psychopathic but mediocre-streaming-series-level famous boyfriend, and the CEO of an aromatherapy/surveillance company whose subscription is a contract only broken by death, maybe. And in “The Jester’s Privilege” (available on Joyland), a young marketing professional working for an image-rehabilitation firm is put on the ISIS account, which is no more or less spiritually fulfilling than anything else in her life.

If all that sounds morbid, I guess it is, but Cash has a way of bringing the humor and humanity of her stories to the forefront. They remind me a bit of what Thomas Pynchon was going for in The Crying of Lot 49, where the absurdity of life is rendered as hyper-real, rather than surreal, except Earth Angel is easier to follow and finds a way to be satisfying. Plus, there’s a genuine playfulness to Cash’s writing, making it a treat to read and re-read.

#3: Real Americans by Rachel Khong (2024)

For me, Rachel Khong’s Real Americans is everything I want in a great novel: A cast of richly drawn characters navigating their relationships with themselves, their family, and the philosophical questions the world forces them to consider; a creative liberty with reality, flirting with the edges of surrealism and science fiction; and a powerful ending that left me in tears.

A multi-perspective story, Real Americans opens with Lily, a young, American-born Chinese woman whose identity stretched between cultures haunts her, and follows her love story with Matthew, an “all-American” man of wealth and status. Then, we shift to their son, Nick, who’s being raised by Lily alone, and follow him as he pieces together why his parents aren’t together and what, if any, relationship he might want with his father. And in the final section, Lily’s mother May takes over, wrestling with her own story of leaving China in the wake of the Cultural Revolution and how the choices she made in America impacted her whole family. Throughout, there’s a steady cadence of secrets and revelations, which almost always create new secrets and questions, and that Khong pulled this all off is, I think, fucking astounding.

#2. Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K. Reilly (2021 [NZ] / 2024 [US])

The moment I finished Greta & Valdin, I texted like every queer fiction reader I know and said something like, “This is the funniest fucking book I’ve ever read, and you should read it, like, yesterday.” Because I am not a total psycho, I did not follow up to see if they’ve read it. But my year end list is here, and now I get to remind not just those friends, but everyone, that this is still the funniest fucking novel I’ve ever read.

Switching between perspectives of its titular characters, Greta & Valdin tells the stories of a brother and sister navigating their love lives and typically-frustrating millennial careers. If that isn’t enough, they’re also constantly — and I mean constantly — dealing with some dramatic flair-up from their sprawling, eccentric family, whose blended Māori-Russian-Catalonian heritage, woven into their intense intellectual and artistic obsessions, keeps everything in motion. Truly, this novel really never stops moving, never hits a low point in the action; thanks to Greta and Valdin’s unique and unfiltered voices, even the most banal interactions are heightened into the sublime.

Greta & Valdin is Rebecca K. Reilly’s first novel, but her boldness in vision and mastery of language have already converted me into a mega-fan. Hopefully, her next novel will get an earlier U.S. release date than Greta & Valdin did, but if not, I’ll suck it up and pay to import a copy from her native New Zealand. It is such a treat to read a writer who’s having as much fun as she’s having (or at least convincing me she’s having), and, again, you should really read Greta & Valdin, like, yesterday.

#1: Penance by Eliza Clark (2023)

In selecting my Top 8 for 2024, it was hard to pick between Eliza Clark’s debut novel, Boy Parts, and her second, Penance. They’re both dark and violent, not in a fetishistic way, but in a way that explores the more disturbing elements of human nature with requisite bite. In the end, I went with Penance, because while Boy Parts is a perfect novel about photography and mental disarray, the sheer ambition and payoff of Penance blew me the fuck away.

Like Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, which Clark suggests Penance is in conversation with, the novel opens on the crime itself, then spends the rest of its narrative arc exploring the aftermath and events leading up to the crime. There’s a meta-textual element, where the “author” of the book is a dodgy true crime writer, Alec Z. Carelli, and the narration is a mixture of his own writing, podcasts about the crime, and “‘primary sources,” and this structure does force the reader to consider their own relationship to true crime. But meta-textual elements like that don’t work unless the actual text delivers, and Penance does.

The crime at the center of Penance is horrific. In a sleepy English seaside town, a teenage girl is burned to death in a beach chalet, although before she dies, she’s able to share the names of her killers: three girls from her school, two of whom she considers (or considered) her friends. But as Carelli digs into the story surrounding the murder, he unearths a complex web of friendships, online communities, and fated relationships that only teenage girls could spin. There are girls who bond over their shared obsession with an American school shooter, girls whose attempts to figure out their sexualities backfire into chaos, and a girl whose Cats fan posts on Tumblr threaten to ruin her reputation at school, which is already dicey since her dad is a right-wing “rent-a-gob" (a fabulous Britishism I learned thanks to Penance, which means a blowhard who shows up in the media all the time, talking their head off ostensibly about politics, but really about their own ego). Like the world we all share, Penance’s world is packed with things happening all the time yet not adding up to what feels like a real, meaningful life, and one can’t help but feel sympathetic for these ultimately murderous girls as they lash out at the world they’ve been born into.

And if you’re concerned about sympathizing with actual murders, you’re safe in Penance. One of the most incredible feats in this novel is how much sheer imaginative force Clark uses to write it. It isn’t based on any one “true crime,” but on Clark’s artistic interpretations of observable patterns in society, made real through her own renditions of them. Truly a masterpiece in my library, and I’m really excited to dig into Clark’s new short fiction collection, She’s Always Hungry, as soon as I have time. (Although perhaps it’s for the best that I didn’t get to that collection before the end of 2024, because then deciding which of Clark’s books to include in my Top 8 might have been even harder.)

And, there you have it! If you’re someone who likes to compare stats, overall, I read 60 books this year, declined to finish 17, and have well over a dozen “in progress.” One of the many reasons I think raw stats are kind of silly is that I’m not going to ding my reading habits over not finishing, say, The Collected Stories of Mavis Gallant or The Basic Readings of Martin Heidegger within some arbitrary deadline of a year’s end. I do think that, in a world where our attention is our most valuable asset, holding oneself accountable to reading is a worthy organizational task, but it’s just a metric. We read for pleasure, for enlightenment, for the chance to see the world through another’s eyes, for the ability to feel feelings that are hard to feel in reality, for escapism, for so many wonderful reasons, it’s impossible to count them all, impossible to jam them into a quantitative framework. However much time you spent this year reading (or listening to music, looking at art, watching good cinema — there’s lots of ways to experience the creative world), I hope it was time well spent.

Cheers,

Emi

PS: If you choose to buy any of the books I’ve shared via the Bookshop.org links inline, I will receive a small commission as an affiliate, because #hustle. Affiliate marketing is objectively gross and weird, but I’m more than happy to exploit the instruments of capitalism to support things I care about: authors, independent booksellers, and book companies that don’t treat their workers like inconvenient placeholders for robotic replacements.

PPS: Yes, I know I promised photographs from Italy, and those are coming! But I tried out one kind of negative scanner and wasn’t satisfied with the results, so now I’m learning a new, more complicated, scanner. My life might be easier if I were the type of person who felt OK sending out subpar scans, but then it wouldn’t be my life, would it?

pushing trespasses and penance up on my tbr because of these reviews!

Nice reviews of these books. Not sure I’ll get to Penance in 25 but your review def made me more interested than I would have otherwise. Also liked how you noted the affiliate links. Great example of how do that in a classy, supportive way.